By UNICEF and Save the Children - Oliver Fiala, Patricia Velloso Cavallari and Seda Karaca Macauley

Ending child poverty is a policy choice and within our reach. But any solutions start with recognizing the problem. Measuring child poverty plays this essential role, driving accountability, fostering policy innovation, and inspiring collective action.

Globally, monitoring child poverty helps create a shared language to compare trends across countries and regions. Reliable, comparable data also enables policymakers to track progress against global commitments, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and to mobilize international support where gaps persist.

But child poverty is not measured in only one way. Definitions vary, as do methodologies and data sets used for producing estimates for monetary and multidimensional poverty. Some rely on income or consumption to estimate household living standards. Others measure complex and often simultaneous deprivations a person can experience across nutrition, education, housing or access to services. These design choices naturally lead to different, yet complementary results.

A recent webinar hosted by the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty brought together experts to summarize the most widely used global estimates. The key takeaways below are aimed at helping practitioners and policymakers to better understand what data exist and how it can drive action.

Source: Save the Children/UNICEF

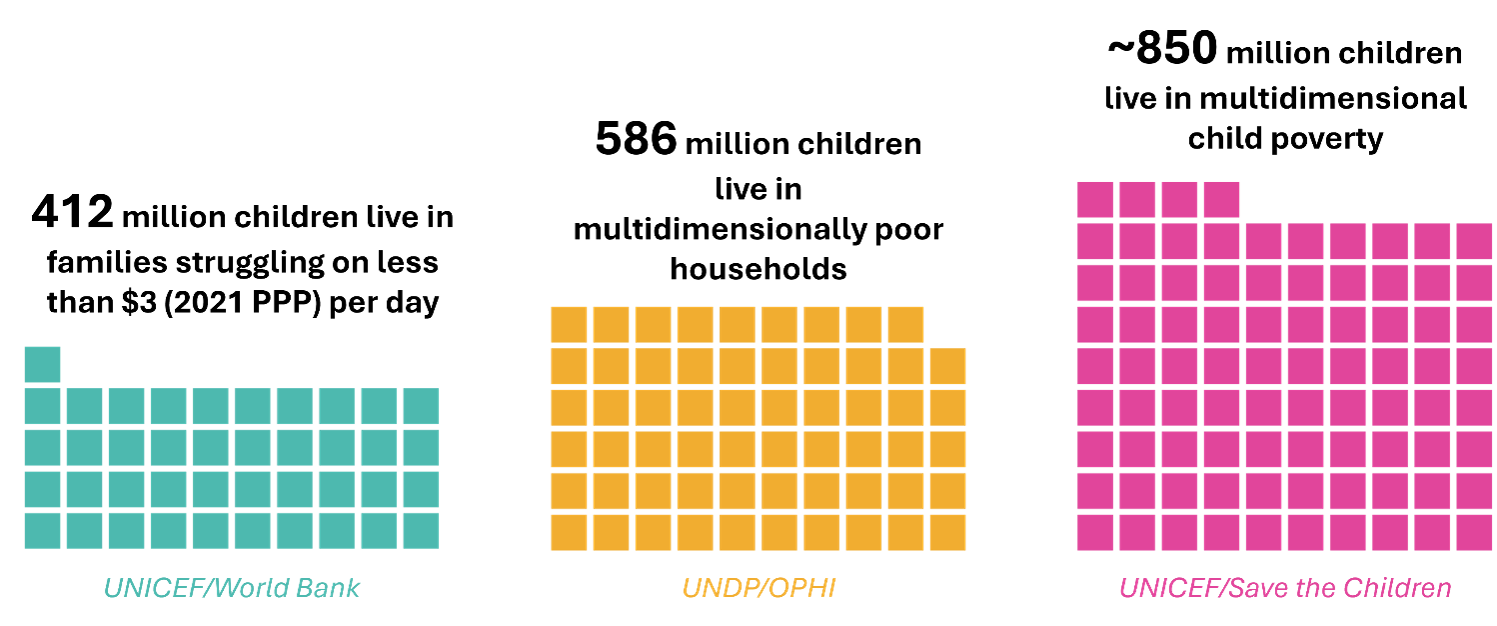

412 million children live in families struggling on less than $3 per day

Gabriel Lara Ibarra, from the World Bank, presented a recent joint paper with UNICEF on monetary child poverty. This method identifies children who live in families where the income per person falls below the International Poverty Line of $3.00 (it also uses a second threshold of $8.20, which better captures poverty in upper-middle income countries). Using comparable household surveys it allows to estimate monetary child poverty across more than 150 countries.

However, because these estimates are calculated at household level, they can’t capture how resources are shared between adults and children within the same family.

586 million children live in multidimensionally poor households

Sabina Alkire from the Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI) shared the latest findings from the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) with a particular breakdown of children who live in multidimensionally poor households. The Global MPI combines ten indicators across health, education and living standards into a single measure, identifying households where overlapping deprivations accumulate.

As with monetary poverty, results are produced at household level. This means all children in an MPI-poor household are considered multidimensionally poor, even though the intensity or type of deprivation may vary between them.

Measuring child poverty directly at the individual child level

Rouslan Karimov from UNICEF Innocenti – Global Office of Research and Foresight presented an alternative approach to measure multidimensional child poverty: developed by UNICEF and Save the Children and using comparable household surveys across countries, this approach measures child poverty directly at the individual child level. This makes it possible to identify children who experience severe deprivations even when they live in households not classified as poor. Findings of this analysis are featured in UNICEF’s flagship The State of the World’s Children 2025 report.

Using the same model in May 2025, the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty estimated that between 850 and 900 million children (nearly 900 million) were living in multidimensional poverty in 2023. With recent methodological adjustments and the inclusion of 2024 data, the updated estimate is now closer to around 850 million.

Different approaches matter

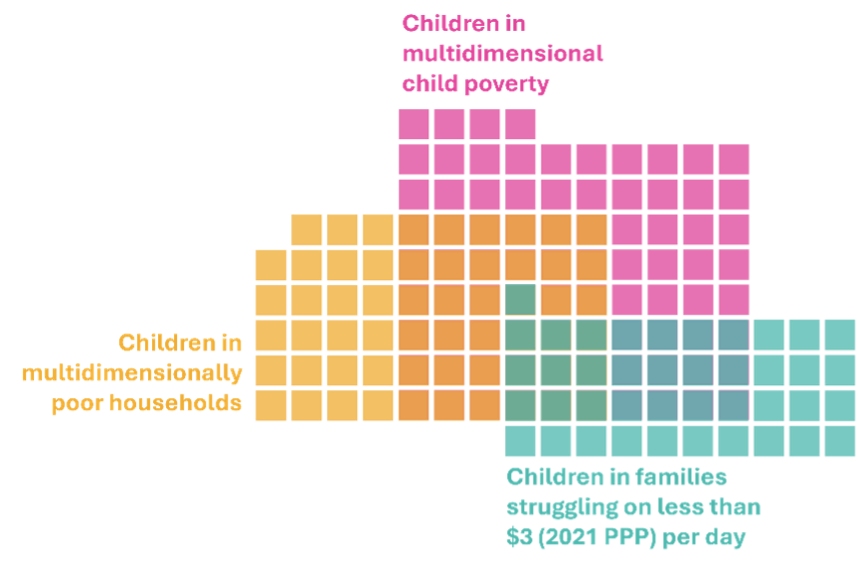

Each of these approaches defines poverty somewhat differently. Because of the differences in construction, each measure answers a slightly different question. Monetary poverty tells us whether families can afford to meet basic needs; the MPI highlights clusters of deprivations that often require multisectoral responses; and the individual measure reveals which children are being missed when household averages mask inequalities.

Source: Save the Children/UNICEF

Something important to note is that these different measures don’t always capture the same children. Examining them together can provide new and more nuanced perspectives.

Although the observations below are based on a quick literature review and some country-specific estimates, they point to three interesting insights about the possible overlaps between the various measures:

Many children who are considered poor also live in multidimensionally poor households. While overlaps vary significantly between countries, focusing on improving key deprivations – education, health, nutrition, housing – helps both children and their families living in poverty.

Many children which experience deprivations may live in households which are not considered multidimensionally poor or which are above the poverty line. Some of this may be a statistical artifact, but it also represents a reality that we can’t always assume child and household poverty go together. This underscores the need for child-specific data, and quality public services.

Some children may not (yet) be deprived, but live in poor households, putting them at high risk of poverty. Social protection can play an essential role in providing resilience and reducing the risk that deprivations at the household level (for instance lack of clean cooking fuel) or family incomes below the poverty line translate into long-term deprivations for children themselves.

Using data to drive action on child poverty

What matters most is to use the data to inform our actions and to improve the lives of children in poverty. Each approach contributes valuable insights – and using them together can help governments understand which barriers matter most in their context: inadequate income, overlapping deprivations, or gaps in access to child-specific services.

We hope that these insights help practitioners, advocates, and policymakers make better use of the different estimates and to strengthen efforts to end child poverty.